Chakki Ka Saag & Dal Baati Churma

Chakki Ka Saag & Dal Baati Churma

A limited menu, and almost total dependence on few key ingredients, has not stopped Marwari food from becoming one of the most popular cuisines of India, discovers MARK MANUEL. |

|

SOMETIMES I think I am a glutton for punishment. My first day in Jaipur, sitting at an al fresco Rajasthani restaurant, I daringly order a Marwari meal for dinner. My knowledge of Marwari food is basic. Dal Baati Churma, Kair Sangri Kumita and Gatta Ki Saag, the top three dishes you will find on menus of Rajasthani thali restaurants everywhere. I strongly suspect that is all that there is to the cuisine, and I am naturally not keen on it. But I figure if a start to a Rajasthani gourmet trail has to be made, it should be with the capital city's premier cuisine. Now I sit back and wonder if I have done the right thing.

Not only are Marwari menus limited to a few dishes and then some, the food is also purely vegetarian. I am amazed to think that people can actually want to be vegetarian in a city where water is scarce, and where vegetables are seen only occasionally. But Marwaris are an enterprising people. If they can carve out an industrial empire in the country out of virtually nothing, to replace green vegetables with cereals, roots, berries and milk, and produce a cuisine that has remarkable variety, was easy! The food, though suggestive of the desert's austerity, is quite supberb, I am about to find out.

My meal starts with Bajre Ki Roti and Lehsoon Ki Chutney. A Rajasthani woman sits in one corner of the restaurant before an open firewood choolah, rolling out the rotis. She also makes rotis of makkai (corn) and gehu (wheat). But Bajre Ki Roti (millet), with Lehsoon Ki Chutney, is the favourite. It is a great leveller in Rajasthan, this dish. Everybody, from the hard-working, lowly peasant to the affluent Maharaja, has it.

Lehsoon Ki Chutney is easy to make. All it requires is a few red chillies, abdundantly grown in Rajasthan, an equivalent amount of garlic and some kanchri (a sour vegetable resembling the tindli). They have another chilli dish to go with rotis, a local green chilli is slit open, stuffed with Rajasthani achari masala and pan-fried. This simple recipe is not a desperately clever measure to pad up the vegetarian menu, the chillies taste awesome!

They use bajra in several other dishes besides the roti (which, really, is so delectable it can be eaten without any accompaniment or just with yoghurt). Like the Bajre Ki Khich � a khichdi made with boiled bajra cooked in a dahi (yoghurt) masala with peas, chopped ginger and a dash of turmeric. Marwaris are fairly crazy about this. They eat it with Chhaach Ka Khata (buttermilk kadi). But the khichdi is not on my menu that night. Instead, I have the Mangodi Pulao, a fragrant Basmati rice Marwari speciality in which the rice is cooked in ghee with a mixture of Rajasthani lentils. The pulao is spiced with cardamoms, cloves, cinnamon, cumin and bay leaves.

And Marwaris use gramflour (besan), wheatflour (chakki) and milk products like yoghurt and buttermilk quite a lot in their cuisine. I am served a small helping of Gatta Curry, or Gatta Ki Saag, a handy, mouth-watering and economical dish from the Marwari chef's point of view. The gatta is a gramflour dumpling (or steamed roll) and it is cooked in a sour buttermilk sauce that is blended with various spices and eaten with pulaos. And after that, the Pithore, again, a dish made of besan, but this one is cooked with yoghurt, a ginger-garlic paste, red chilli powder, turmeric, chopped coriander, ginger and green chillies, and in ghee over a double boiler, to become hard like a barfi.

I think the piece de resistance of Marwari creativity comes out best in the Chakki Ka Saag, a chewy, exotic food based in another spicy yoghurt shorba. Delighted with my reception to it, the chef comes out of the kitchen to reveal its recipe: "Take half a kilo of wheat flour, preferably the red variety which has more elasticity, and knead it into a loose dough. Leave some water in it and let it stand for half an hour.

Then, wash and scrub it under a tap of flowing water until you are left with a quarter of the dough. After some more kneading and stretching, making it spongy to the touch, add a pinch of garam masala, red chilli powder and salt, and mix well. Break of little pieces and fry them like pakoras. The yoghurt curry is made in pure ghee. Onion is given vaghar in the ghee and garam masala, ginger-garlic paste, chilli powder, dhania, haldi, salt and the yoghurt are added and bhunaoed. It will taste like non-veg!" Gee! And I though I was eating some exotic meat preparation.

Marwaris who used to serve the royal families of Udaipur, Jaipur, Jodhpur, Bikaner and Jaisalmer, and who did not want to be left behind, tried to emulate the cusines of their masters. Since meat was taboo, they invented dishes like Chakki Ka Saag and Gatta Ki Saag which closely resembled exotic meat dishes. Different communities have preserved their own culinary traditions and conventions. The Maheshwaris, Jains, Vaishya and Gaur Brahmins practice vegetarianism in its most pristine form. Don't confuse this with spartan asceticism. It has a dazzling range of subtle and satisfying dishes. It was at the homes of the Maheshwari merchants, a community that eschew even roots (because they excite passions!), that vegetarian delicacies of stunning sumptuousness were developed.

The accent in their vegetarian cuisine is on purity of ingredients and richness (ghee, mawa and exotica). To their credit, these communities have balanced this penchant for rich foods with the appropriate use of digestives, especially asafoetida, black rock salt, ginger and ajwain. Their favoured spices are fenugreek seeds, qasoori methi (dried fenugreek leaves) and aniseed. The favourite snack is the Panchkuta, which has five basic ingredients � Sangri (radish pods), Kair and Kumita (both wild berries), dried red chillies and whole amchur (dried mango) cooked in oil and basic masalas.

And Marwari cuisine's signature dish, the ubiquitous Dal Baati Churma, which is a feast in the winter. The dal is a mixture of the split black urad dal and channa dal, but sometimes it is also arhar or tur dal, and it is given a ghee tarka. Baatis are atta balls made of refined wheat flour. They are roasted over slow cowdung fires to become hard and brittle. It takes half an hour for the baati to get cooked, then it is almost too hot to consume! When a baati is mashed up in ghee, and it is mixed with jaggery, crushed cashew nuts, pistas and caster sugar, to become a coarse powder, it is called churma. Break another baati in the churma, pour dal over it, some ghee, make a mish-mash with your hands and feed yourself the first mouthful.

I am told that food in -Rajasthan is considered 'prashad' and 'tabarrukh', and that the bounty of the land is meant to be shared with others. The 'satvik' (spiritual) tradition, here, is as strong as the 'rajsik' (noble/heroic). With a climate which is harsh and inclement, the therapeutic element � Ayurvedic and Unani � is considered as important as the aesthetic. 'Guna/tahseer' (intrinsic qualities) of ingredients is accorded priority. The extensive use of turmeric, asafoetida, cumin, pepper, coriander and red chillies is for specific aperitif, digestive and carminative effect.

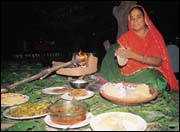

The chef rolls out with a traditional Marwari thali. I look at him in disbelief. "You must experience it," he implores. Then goes on to explain, "Arranged from right to left is a papad, there's Kair Sangri Kumita, it grows in the desert once a year, is eaten fresh or dried and stored away, then there's Shahi Paneer, yes, we do a paneer in Rajasthani food as well, and Bela, you might not like it because it's too oily; the next is a Kadi and then there's Dal Fry, they look the same, but the Kadi's got yoghurt.

We offer an assortment of breads, there's the atta chapati, a tava paratha, and the misi (besan) roti. The thali must have some namkeen, and that's there. The desserts are Misri Mava and Rasmalai. Plus, the savoury, Dahi Wada, and Marwari cuisine's famous Panchmela... it's got beans, bhindi, cabbage and other seasonal vegetables. If you want, I can thrown in a soup, a paprika soup. And a veg. pulao. Yes, no?"

I could see he was disappointed my by dismal appetite for Marwari food. But optimistically, he promises to do me a thali the next day. Tomorrow is another day, he assures me. "Yes," I tell him, "and I shall feast exclusively on the meat dishes of Jaipur's Rajput cuisine!"

|

Home Page

About the mag

Subscribe

Advertise

Contact Us