|

|

|

THE recitation of Gurbani filled the air as I parked my car in the vicinity of the Golden Temple in Amritsar and prepared to enter the holiest Sikh shrine in the world. The Harmandir Sahib or the Abode of God, popularly known as the Golden Temple, is a living symbol of the spiritual and historical traditions of the Sikhs. It has been a source of inspiration to the community, and a place of pilgrimage, ever since its establishment in the 16th century. But I was not going there out of faith or devotion. Nor was I going to marvel at the architectural splendour of its gold domes and minarets, its ornate marble hallways, where the Sri Guru Granth Sahib, the sacred writings of the Guru and other revered saints, is the central object of Sikh worship. I was drawn to the Golden Temple by the Guru Ram Das Langar, the community kitchen, which offers a free meal to everybody who visits the gurudwara without consideration of caste, colour, creed or status in society. This practise is an institution in Sikhism. And one I admire. Visitors to the Golden Temple are required to cover their heads and take off their footwear all the time they are inside, and I complied with the decorum, dipping my feet in a small water channel to wash them before entering the temple complex. I am told that the construction of the amazing edifice began in 1559, and that there is great significance in its design; the Harmandir is located in water, and this symbolises nirgun and sargun, the spiritual and temporal realms of existence. And with its base situated lower than the surrounding land, the gurudwara emphasises the faith's inner strength and confidence; the visitor has to go down steps in order to pay homage at the shrine, which is intended to teach Sikhs to be full of humility at all times. The Harmandir is also open on all four sides, signifying that the temple is open for one and all.

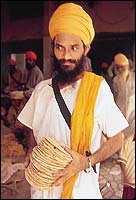

I thought that I had seen some large kitchens in the world, but the one at the Golden Temple in Amritsar is something else. It is enormous, like three basketball courts, and as active as ten. Everywhere I looked, people were energetically occupied in some form of cooking. The main enterprise being making rotis. Hundreds of women sat on the floor and rolled out rotis and tossed them onto big, flat hotplates that were fired from beneath by gas pipes. Roasting the rotis was done by men. With long, hooked rods, they sat like boatsmen with oars, expertly flipping the rotis over one by one, and then scooping them off the hotplates and into baskets kept by the side. Other men picked up these baskets and rushed out to the eating area where at a time, thousands of visitors to the Golden Temple sit and eat together. They were devotees who spared some time from their obligations and sat and rolled out rotis or cooked the dal and sabzi for the day. No, they didn't get paid! It was service to God. For that you can scarcely expect payment, Ranjit Singh said. "Go inside, see how it is done," he encouraged me. "But do keep your head covered at all times and take off your shoes." I walked around unhindered.

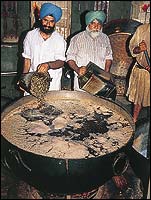

The men stirring the dal in the biggest handis of my experience invited me to join them in the activity. And I would have, but the heat from the fires was so intense that I involuntarily stepped back. Altogether, they were an industrious lot. And to think they were all strangers working together to feed another lot of strangers. Ranjit Singh informed me that the vegetables, flour, ghee, lentils and other ingredients were bought from local contractors in Amritsar and stored at the Golden Temple. At any given time, the Guru Ram Das Langar had enough rations to last for three months. Which I thought was pretty amazing, because on an average, the langar fed 70,000 people every day, and on Sundays and festive occasions, the figure went upto 1,50,000 and even 2,00,000. But what was the need to store so much of food, I asked Ranjit Singh. And he replied gravely, "For a crisis." He was not just talking about the Golden Temple in Amritsar, but a crisis outside the city and state as well. "Like the Gujarat earthquake," he said. "Lot of food went from here. We sent volunteers with tons of dry rations to feed the victims." I understood what he meant then. The food, and the langar itself, was being run entirely on the donations the Shiromani Gurudwara Prabhandhak Committee, which looked after the temple, collected. Most of what it got, the committee pumped back into the running of the Golden Temple. There is no fixed lunch or dinner hour at the Guru Ram Das Langar. It is always meal time here. You collect a plate and glass and take your place in one of the large dining halls between the beggar and Maharaja from the neighbouring state. Volunteers rush up and down the rows of seated people serving the dal-sabzi-roti-kheer meal out out aluminium buckets and cane baskets. While this is going on, nobody is supposed to eat, and one Sikh walks between the rows loudly calling, "Satnam Wahe Guru!" Which means, "O wondrous Lord, Your name is true". Then when the service is finished, and everybody has been served the complete meal, the marching Sikh calls out even louder, "Bole So Nihal..." And the thousands of people waiting to start eating respond in one voice with a roar, "Sat Sri Akal!" Which means, "Anybody who takes God's name becomes pure." At this, you may start eating. And you may eat hearty, because nobody is required to get up until he is satisfied and full. I witnessed one entire pangat go through its meals and realised that what I was seeing in that holy place, was nothing short of a miracle. For thousands to be fed on a day to day basis even the simplest of meals, must take a miracle to achieve.

"No," I replied, "I am here on work." "Come, come," he said, leading me back to the dining hall. "In Amritsar nobody goes to sleep hungry."

|

Home Page

About the mag

Subscribe

Advertise

Contact Us

At the Golden Temple,There's Always A Meal For The Hungry

At the Golden Temple,There's Always A Meal For The Hungry

I'll admit, I was overwhelmed with the feeling that I was treading on holy ground. The noise and the bustle of Amritsar outside had melted to give way to a solitude and quietness of this place of legends and miracles. I recognise architecture and from what I could make out of golden turrets, domes and minarets, reflecting vividly in the pond of holy water (amrit, from which the city gets its name) and shining in the bright afternoon sunlight, I'd say the Harmandir is a mixture of Mughal and Rajput work. The two-storied gurudwara rises majestically out of this pond, its marble floors so spotlessly white that you can eat off them, and this despite thousands of visitors walking barefoot there every day. Entry to the temple itself is from a long, narrow promenade across the pond. I did that, I made my entry for the sangat, the holy congregation, then came out and headed for Guru Ram Das Langar for the pangat, the sitting for food. At the Golden Temple, there is no such thing as

lunch hour and dinner hour. It's always meal time here.

I'll admit, I was overwhelmed with the feeling that I was treading on holy ground. The noise and the bustle of Amritsar outside had melted to give way to a solitude and quietness of this place of legends and miracles. I recognise architecture and from what I could make out of golden turrets, domes and minarets, reflecting vividly in the pond of holy water (amrit, from which the city gets its name) and shining in the bright afternoon sunlight, I'd say the Harmandir is a mixture of Mughal and Rajput work. The two-storied gurudwara rises majestically out of this pond, its marble floors so spotlessly white that you can eat off them, and this despite thousands of visitors walking barefoot there every day. Entry to the temple itself is from a long, narrow promenade across the pond. I did that, I made my entry for the sangat, the holy congregation, then came out and headed for Guru Ram Das Langar for the pangat, the sitting for food. At the Golden Temple, there is no such thing as

lunch hour and dinner hour. It's always meal time here.

Camera in hand, my nostrils twitching with the smell of wholesome food cooking, I walked around fascinated.

The Golden Temple's langar, which means community kitchen, is named after the fourth guru of the Sikh community, Guru Ram Das. It is operational 24 hours a day, 365 days a year, and it is open to everybody who comes to the Golden Temple... devotee, tourist, curiosity-seeker. Anybody can have a meal there free of charge. What is amazing is that the entire operation is run by volunteers. Ranjit Singh, a burly Sikh who looks after the kitchen, told me that the langar had only ten professional cooks and about 20 helpers. Everybody else was a volunteer.

Camera in hand, my nostrils twitching with the smell of wholesome food cooking, I walked around fascinated.

The Golden Temple's langar, which means community kitchen, is named after the fourth guru of the Sikh community, Guru Ram Das. It is operational 24 hours a day, 365 days a year, and it is open to everybody who comes to the Golden Temple... devotee, tourist, curiosity-seeker. Anybody can have a meal there free of charge. What is amazing is that the entire operation is run by volunteers. Ranjit Singh, a burly Sikh who looks after the kitchen, told me that the langar had only ten professional cooks and about 20 helpers. Everybody else was a volunteer.

It is true, the Sikhs are among the friendliest people of the world. Nobody frowned at my presence. Nobody turned his or her face away from my camera. In fact, they were happy to stop whatever they were doing and let me get my pictures. Like the old man who was going about delivering small mountains of freshly kneaded dough to the women who were making rotis. And the other ancient who was doing the kneading in a small room using a large machine. Also the crippled young Sikh whose job it was to deliver rotis from the cooking area to the dining. Or the beautiful but shy teenage Sikhni who sat rolling out rotis with her head lowered all the time.

It is true, the Sikhs are among the friendliest people of the world. Nobody frowned at my presence. Nobody turned his or her face away from my camera. In fact, they were happy to stop whatever they were doing and let me get my pictures. Like the old man who was going about delivering small mountains of freshly kneaded dough to the women who were making rotis. And the other ancient who was doing the kneading in a small room using a large machine. Also the crippled young Sikh whose job it was to deliver rotis from the cooking area to the dining. Or the beautiful but shy teenage Sikhni who sat rolling out rotis with her head lowered all the time.

And that this is being done entirely though a voluntary service, makes it even more remarkable. When everybody had finished, there was no mad scramble to get up and go. Instead, the devotee and the visitor, the beggar and millionaire, all walked in great discipline to where facilities were available for each one to wash his or her own plate. You didn't want to do that, no problem, there was a relay of volunteers standing in formation to convey the dirty dishes to the wash area. You washed your hands, had a glass of crystal clear, purified water, and then made your way out. And I was doing just that when Ranjit Singh stopped me. "Have you eaten as yet," the caring Sardar asked.

And that this is being done entirely though a voluntary service, makes it even more remarkable. When everybody had finished, there was no mad scramble to get up and go. Instead, the devotee and the visitor, the beggar and millionaire, all walked in great discipline to where facilities were available for each one to wash his or her own plate. You didn't want to do that, no problem, there was a relay of volunteers standing in formation to convey the dirty dishes to the wash area. You washed your hands, had a glass of crystal clear, purified water, and then made your way out. And I was doing just that when Ranjit Singh stopped me. "Have you eaten as yet," the caring Sardar asked.