The Shrewsbury Fix!

The Shrewsbury Fix!

Nobody visits Pune and comes back without a packet of the famous Shrewsbury biscuits, writes ALKA KSHIRSAGAR, not even the prime minister of India. For the citizens of Pune, the famed biscuits are a mid-morning fix. Try getting it, however! |

|

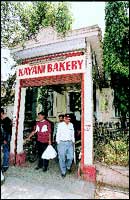

WHEN your clientele includes some of the country�s most famous names � Dilip Kumar and the (Raj) Kapoor clan for instance � it�s not surprising that you�ll have some interesting tales to tell. But the Kayanis� all time favourite reminiscence is of the time when the Maharashtra Police equivalent of the Black Maria screeched to a halt in front of their bakery many evenings ago.

A couple of policemen jumped out of the van and headed straight for the counter, making it clear that they weren�t going to allow the jostling crowds to impede their assignment. Their mission? To collect a few kilos of the Kayani brand of Shrewsbury biscuits for the visiting prime minister himself. He happened to have had them over tea at an inaugural function in Pune, and had specially requisitioned for them, they explained.

Their urgency was understandable. You don�t allow biscuit consignments to hold up prime ministerial planes. Somewhat more importantly, you don�t want to have to sheepishly confess to the boss that by the time you arrived, the bakery had no Shrewsbury biscuits left on its shelves.

Yes, the masters of a product-line that has, for years, been flying off the shelf, are glad that customers think their biscuits are the crunchy-crumbliest, their cakes light as a cloud, and their melting-in-the mouth khari, well, the mouth-meltingest. But expansion? No sir, not on the cards as yet.

Getting the fiercely media shy, low-profile, work-is-a-religion Kayanis to talk about the bakery at all is a challenge. Getting them to do so during peak hour (11 a.m to noon) when customers are clamouring at the counter for the just-baked buns, biscuits and cakes is, if anything, a greater challenge.

I manage to convince Farokh to give me a few minutes. We wander inside the spacious, reminiscent-of-the-50s, front end of the bakery, to the working area behind. Weaving through trayloads of divine smelling goodies, and Italian marble topped wooden work-tables, just about finding enough unoccupied space in the 7,000 square feet bakery that also houses the godown, to squeeze in a rickety chair and a stool.

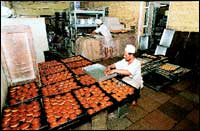

Firdaus, dressed for work in shorts and T-shirt, escorts me round the place. The first few batches of goldbrown Shrewsbury biscuits are being pulled and a fresh lot of trays are ready to be put in. Even as workers sit cross-legged on the well-scrubbed floor, shaping lemon-sized balls out of the prepared dough, which are then �stamped� into shape.

Nestling below the marble topped tables on one side are four wooden vats that hold the zymurgycal secret to the famous Kayani bread � the original yeast culture, that has been undergoing continuous chain reaction for 30 years! �Everyday, we add hops, water, sugar and flour for the fermentation to continue,� Firdaus explains, adding that the bread has �no whitener, no chemicals and no risener.�

The exact proportion of the ingredients that go into the making of the various products are a tightly guarded secret, and everything except the cakes are entirely hand-mixed. The six of them � the four others being Rustom, Parvez, Sohrab and uncle Noshir � work in shifts taking care of the purchasing, selling and mixing themselves, even weighing out the ingredients and preparing the dough for the Shrewsbury biscuits. All that Firdaus is willing to volunteer is that the egg-free biscuits are prepared exclusively from Amul butter. �First it used to be Polson, now it�s Amul. It there�s no Amul, we just stop making Shrewsbury,� he grins.

The Kayani family migrated to India from Iran in the early 20s, and the brothers Hormuz, Khodayar and Rustom worked at the Royal Bakery on Main Street (that still exists) for some time before setting up their own bakery in 1954.

Curiously, none of the Kayani women ever venture near the bakery. It�s been an �only men policy� since his grandfather�s time, Firdaus chuckles, and indicates that things aren�t about to change. The only impending one is that two of their (male) offspring are taking professional courses in baking and confectionary and may eventually spearhead some changes.

Till then the Kayanis are content to be silent and lowkey and let their cakes and cookies do all the talking! |

Home Page

About the mag

Subscribe

Advertise

Contact Us

But try suggesting to the six Kayanis, spanning two generations, who jointly hold the reins at the soon-to-be-50 Kayani Bakery on Pune�s East Street, that its time to put expansion plans into first gear. (Particularly since you can�t always make it to Kayani Bakery by 5 p.m. to get a clutch of their famed biscuits.) All you�ll get in reply is a shrug, a smile, and probably, a shake of the head.

But try suggesting to the six Kayanis, spanning two generations, who jointly hold the reins at the soon-to-be-50 Kayani Bakery on Pune�s East Street, that its time to put expansion plans into first gear. (Particularly since you can�t always make it to Kayani Bakery by 5 p.m. to get a clutch of their famed biscuits.) All you�ll get in reply is a shrug, a smile, and probably, a shake of the head. To the left of the large room are the two ovens, wood-fired, that work 24 hours a day, six days a week. (Sunday�s their day of rest.) �Electric supply is unreliable, and the wood lends a flavour to the cakes and biscuits,� Farokh explains. He has just begun to tell me the genesis of the Kayani tale of success when his nephew (his cousin�s son) Firdaus walks in and joins in on the conversation. Before we know it, Farokh beats an escape, and I can swear it, he looked relieved.

To the left of the large room are the two ovens, wood-fired, that work 24 hours a day, six days a week. (Sunday�s their day of rest.) �Electric supply is unreliable, and the wood lends a flavour to the cakes and biscuits,� Farokh explains. He has just begun to tell me the genesis of the Kayani tale of success when his nephew (his cousin�s son) Firdaus walks in and joins in on the conversation. Before we know it, Farokh beats an escape, and I can swear it, he looked relieved.  The bakery works in two shifts, preparing the salted products � white and brown bread, rolls, buns, surty butter, elaichi butter, cheese papdi, the goldenest khari � during the night while the biscuits and confectionary � choco walnut/madeira/mawa cakes and ginger/brazilnut/coconut biscuits are made during the day.

The bakery works in two shifts, preparing the salted products � white and brown bread, rolls, buns, surty butter, elaichi butter, cheese papdi, the goldenest khari � during the night while the biscuits and confectionary � choco walnut/madeira/mawa cakes and ginger/brazilnut/coconut biscuits are made during the day.