Ganga Jal, The Water Of Life

Ganga Jal, The Water Of Life

The waters of the Ganges are sacred and said to be rejuvenating. A dip in the river is the dream of every Hindu. And to die on its banks is an assurance of a berth in heaven. SHABO KHAN explores the myth behind the Holy River. |

|

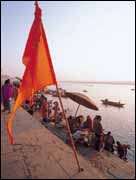

IT is just after the crack of dawn on the Ganges and the boatman, Shivprasad Singh, touches my arm and points out the Manikarnika Ghat that is looming up in the darkness. He need not have bothered. I could smell the firewood long before I saw the bodies burning in the pinkish-yellow glow that gently bathes Banaras in the sunrise hour. This is the most sacred of the ghats in Banaras, and the oldest. It is also the central ghat that divides the city into two.

I count the bodies. There are five. And I can see at least three more lined up for cremation. I also see huge dark shapes creeping upon us in the Holy River. They are boats with people like me come to capture the Hindu way of life. I hope fervently that they can see us too in the dark, because I don't fancy being overturned into the cold waters. These sort of accidents are known to happen. "Are there crocodiles here," I hesitantly ask Shivprasad. He grins, a flash of white in a Cherry Blossom face, "Not here, but up the river. And if you fall in, so what! The waters are sacred, you will come out purified."

The Holy River is personified as a sustainer of life. Her waters are said to purify all those who step into them. The faithful believe that a mere glance at the Ganges can bring peace and solace. And for at least two million years, they have been coming here from every corner of India to stand waist-deep in the waters, hands raised heavenwards as if to invoke Lord Shiva or whichever god they worship, voices raised in prayer. While behind, on the many ghats, temple bells ring and sadhus chant, and the smell of incense from sacrificial offerings mixes with the aroma of jelebis being fried in ghee for breakfast.

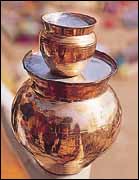

I see people carrying away Ganga Jal in copper and earthenware vessels for various rituals at home. I am told the holy water will also be used in cooking. Banarasis believe that food becomes divine when cooked in Ganga Jal. Perhaps they are right, because the food in Banaras, the Satvik vegetarian cuisine that is not drowned in spicy masalas or onion and garlic, tastes like nothing else in this country. Tea addicts are known to swear that their daily cuppa� tastes like heavenly nectar, like amrit, when brewed in Ganga Jal. Is this all a matter of faith? Or does the waters of the Ganges really have magical

properties?

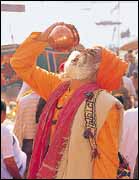

Nobody thinks the waters might be polluted by all those devotees bathing there and washing their clothes. By the refuse and ash of cremated bodies washed off the ghats twice a day into the river. Or by the corpses pushed into the flowing waters by poor people who cannot afford cremations. One sadhu I daringly chat up with asks me how can the waters that are all-purifying be polluted? Then he offers an explanation: "Maybe because it is continuously flowing, there is no pollution in the Ganges." And a revelation. "There is no sedimentation, you can store Ganga Jal for however long you want, it will always remain fresh."

Shivprasad Singh, my boatman and guide, tells me that the holy water, when applied on the tongue of a dying Hindu anywhere in India, or the world, brings absolution from sin. That's why most Hindu families keep a little jar of it at home. Then he leads me to the Dashashwamedha Ghat where enterprising hawkers are selling small take-away copper pots of Ganga Jal for such purposes. A pot containing 500 ml of the holy water costs Rs. 50. There are smaller ones for Rs. 50 and Rs. 40, and a set of four tiny pots for Rs. 80. I buy all the sizes. The hawker, a wizened, toothless old man, beams. I don't know what I will do with the Ganga Jal, but strangely, its very presence in my kitchen at home is

comforting.

|

Home Page

About the mag

Subscribe

Advertise

Contact Us

In that lies the legend of the Ganges. To the devotee and to the tourist, the Ganges is not a river. She is a mother deity with the power, the shakti, to offer absolution from sin and freedom from the cycle of rebirth. The myth of the Ganges' origin, her descent from heaven onto Lord Shiva's (the presiding deity of Banaras) matted hair, represented by the towering peaks of the Himalayas, where he contained her tempestuous flow and finally released her waters into the plain-land, represents the origin of riverine civilisations in pilgrim cities such as Banaras, Hardwar and Allahabad.

In that lies the legend of the Ganges. To the devotee and to the tourist, the Ganges is not a river. She is a mother deity with the power, the shakti, to offer absolution from sin and freedom from the cycle of rebirth. The myth of the Ganges' origin, her descent from heaven onto Lord Shiva's (the presiding deity of Banaras) matted hair, represented by the towering peaks of the Himalayas, where he contained her tempestuous flow and finally released her waters into the plain-land, represents the origin of riverine civilisations in pilgrim cities such as Banaras, Hardwar and Allahabad.

Indeed, I remember reading that the country's Mughal rulers, from Muhammad-bin-Tughlak to Akbar and Jahangir to Aurangzeb, kept Ganga water in their kitchens at Delhi and Agra for its medicinal properties. And that British physicians were amazed to find that vessels of the river's waters that were kept sealed in Hindu homes remained unspoiled for decades. Experimental studies have shown that the holy water has an unusual capacity for self-purification, and is exceptionally lethal against bacteria and cholera germs. Organic pollutants discharged into the Ganges were removed 10 to 25 times faster than any other river in India. And three causes were reported for this activity. The presence of bacteriophages which are deadly to many organisms (mosquitoes, for example, cannot breed in the Ganges); the presence of heavy materials like silver, copper, iron, chromium and nickel; and, the presence of minute quantities of radio-active materials such as Bismuth-24.

Indeed, I remember reading that the country's Mughal rulers, from Muhammad-bin-Tughlak to Akbar and Jahangir to Aurangzeb, kept Ganga water in their kitchens at Delhi and Agra for its medicinal properties. And that British physicians were amazed to find that vessels of the river's waters that were kept sealed in Hindu homes remained unspoiled for decades. Experimental studies have shown that the holy water has an unusual capacity for self-purification, and is exceptionally lethal against bacteria and cholera germs. Organic pollutants discharged into the Ganges were removed 10 to 25 times faster than any other river in India. And three causes were reported for this activity. The presence of bacteriophages which are deadly to many organisms (mosquitoes, for example, cannot breed in the Ganges); the presence of heavy materials like silver, copper, iron, chromium and nickel; and, the presence of minute quantities of radio-active materials such as Bismuth-24.