Khaiyke Paan Banaraswala!

Khaiyke Paan Banaraswala!

One thing that symbolises the Banarasi's addiction to good things of life, is paan. The joy of eating Banarasi paan is indicative of the joy of moksha... which is spiritual enlightenment, says YOGESH ALAKNANDA. |

|

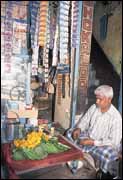

AMITABH BACHCHAN got it right in Don when he sang and danced with such gay abandon about the fabled paan Banaraswala. It does open up the recesses of even the dullest mind. I am finding this out as I get deeper in conversation with Chottelal Kesri of Krishna Paan Bhandar near the Nadesar Palace Grounds in Banaras. He's the local paan hot-shot and nobody makes a Banarasi better than he does in this area. Thankfully, he's quite sharp and with-it, and is impressively savvy about his business. It would not do to have a Banarasi paanwalla who was a dullard after Amitabh's testimonial in Don.

But yet the paan, says Chottelal Kesri, enjoys a positive and health-giving status in Banaras and is an easy-to-come-by and all-season delicacy. Eating a paan, folding it with spices and condiments and sharing it with a friend, is a gesture of hospitality. Visiting the roadside paanwalla to buy a paan and eating it leisurely, is a way of life. It is a habit that has been cultivated all over India. But in Banaras, paan is a habit with a deep social significance. Hearing Chottelal Kesri extolling the virtues of paan, I am inclined to think it is like wine and cheese with the French. Or tea and sake with the Japanese.

The genuine, red-lipped Banarasi will also claim to be able to identify from which paanwalla in his city a paan has come just by sniffing the fragrance emanating from it. And likewise, the paanwalla knows his customer. Some will have their paan only with the basic ingredients, the katha, chuna and supari, each paanwala adjusting the proportions of the ingredients to suit the customer's taste. Some customers who don't get their kick from tobacco, will ask in the winter months for their paan to be made also with poppy seeds. What happens? "It produces a tingling, burning sensation in the ears and beads of perspiration on the forehead," says Chottelal Kesri.

He sells three varieties of paan: the Sada, with katha, chuna and supari, at Rs. 2 a paan; the Singada or Giloda paan without varq (edible silver foil) at Rs. 3; and, the Special Chandiwala

The paan leaf, the paan chewer, the paan stall and the paanwalla, are all a common sight in Banaras and an indelible part of the cuisine here. There is an auction market, a paan dariba, where paans from all over India arrive at 7 in the morning. It is a beehive of activity. Paans are auctioned in dholis, bundles, of 200 leaves each. They are sold by farmers or sometimes middlemen to paanwalas. The magahi leaf sells for upto Rs. 150 for a bundle of 200, while other leaf types fetch upto Rs. 50 a dholi.

|

Home Page

About the mag

Subscribe

Advertise

Contact Us

Everywhere in Banaras I have been told and have read, that it is the simple pleasures of life that give the man from this holy city the strut in his walk. Like a bath in the river, a visit to his favourite temple, meeting friends over music, mithai and thandai. And the paan. Yes, paan symbolises the Banarasi's addiction to the good things of life like none of the rest do. And this addiction, an outsider will say, is virtually over nothing. There's a betel leaf, supari (arecanut), katha (catechu), chuna (lime), gulkand (rose jam), honey-flavoured elaichi (cardamom), and for those who want it � tobacco.

Everywhere in Banaras I have been told and have read, that it is the simple pleasures of life that give the man from this holy city the strut in his walk. Like a bath in the river, a visit to his favourite temple, meeting friends over music, mithai and thandai. And the paan. Yes, paan symbolises the Banarasi's addiction to the good things of life like none of the rest do. And this addiction, an outsider will say, is virtually over nothing. There's a betel leaf, supari (arecanut), katha (catechu), chuna (lime), gulkand (rose jam), honey-flavoured elaichi (cardamom), and for those who want it � tobacco.

The paan is closely connected to the Banarasi way of life. They make a production number out of chewing paan. Infinite pains are taken over the preparation of their paan. And in each household, there will be a different kind of paan flavoured with ingredients known only to the family and varied according to the season. The leaf has to have just the right degree of softness and the ingredients that go into the paan have to mixed in just the right proportions. The ideal paan, a Banarasi will say, is the one that dissolves in the mouth without being chewed. And he will boast that a true Banarasi may be identified from the way in which he makes, receives and offers paan. Perhaps.

The paan is closely connected to the Banarasi way of life. They make a production number out of chewing paan. Infinite pains are taken over the preparation of their paan. And in each household, there will be a different kind of paan flavoured with ingredients known only to the family and varied according to the season. The leaf has to have just the right degree of softness and the ingredients that go into the paan have to mixed in just the right proportions. The ideal paan, a Banarasi will say, is the one that dissolves in the mouth without being chewed. And he will boast that a true Banarasi may be identified from the way in which he makes, receives and offers paan. Perhaps.

Singada for Rs. 5. What is a typical Banaras paan? It is a paan in which the betel leaf used is the tender magahi leaf from Bihar. This is eaten in its primal green or off-white condition. You can have a Banarasi paan with tambakhu (tobacco) or meetha (sweet). Chottelal Kesri describes the tambakhu variety. The supari is soaked in water and cracked into small pieces or made into shavings. Limestone is also soaked in water and laboriously ground to soften the acidic burn. Sometimes, it is mixed with milk, yoghurt or butter. The bark of the catechu tree is boiled to extract its secretion, the katha. It is then mixed with rose water or kewra water, screwpine, for flavouring. Camphor is added, and cloves, aniseed, nutmeg, saffron, poppy seeds, grated coconut, musk and kimam (tobacco paste).

Singada for Rs. 5. What is a typical Banaras paan? It is a paan in which the betel leaf used is the tender magahi leaf from Bihar. This is eaten in its primal green or off-white condition. You can have a Banarasi paan with tambakhu (tobacco) or meetha (sweet). Chottelal Kesri describes the tambakhu variety. The supari is soaked in water and cracked into small pieces or made into shavings. Limestone is also soaked in water and laboriously ground to soften the acidic burn. Sometimes, it is mixed with milk, yoghurt or butter. The bark of the catechu tree is boiled to extract its secretion, the katha. It is then mixed with rose water or kewra water, screwpine, for flavouring. Camphor is added, and cloves, aniseed, nutmeg, saffron, poppy seeds, grated coconut, musk and kimam (tobacco paste).

Ayurveda indicates that paan has medicinal properties. It is carminative, anti-bacterial, cough-repelling, enhances facial beauty, and keeps one fit. Like other gourmet delights, the Banarasi believes that the paan also contributes to image and atmosphere. It is also a subtle aphrodisiac and poets and healers vouch for its patent goodness. Chottelal Kesri swears that if people look upon paan as a flavour, an oral stimulation, as food, as well as an artefact of a particular culture, they would understand more of the Indian way of life. One last question. Why is one paan swallowed and consumed, and one spat out? He chews for a while, rolling the paan in his mouth before spitting it out in a stream of furious red. "Many paans are made today with dollops of gulkand and honey-flavoured cardamom and supari, and are really like sweetmeats, to be eaten like chocolates! Connoisseurs look upon these with disdain," he says scornfully.

Ayurveda indicates that paan has medicinal properties. It is carminative, anti-bacterial, cough-repelling, enhances facial beauty, and keeps one fit. Like other gourmet delights, the Banarasi believes that the paan also contributes to image and atmosphere. It is also a subtle aphrodisiac and poets and healers vouch for its patent goodness. Chottelal Kesri swears that if people look upon paan as a flavour, an oral stimulation, as food, as well as an artefact of a particular culture, they would understand more of the Indian way of life. One last question. Why is one paan swallowed and consumed, and one spat out? He chews for a while, rolling the paan in his mouth before spitting it out in a stream of furious red. "Many paans are made today with dollops of gulkand and honey-flavoured cardamom and supari, and are really like sweetmeats, to be eaten like chocolates! Connoisseurs look upon these with disdain," he says scornfully.